Mexico is notoriously one of the most dangerous countries for journalists. But the consequences of targeting journalists in Mexico extend beyond murders.

When journalists are killed, forced to flee, or quit the profession, “zones of silence” are created — a consequence of self-censorship or displacement due to threats, causing information gaps in their communities, according to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR).

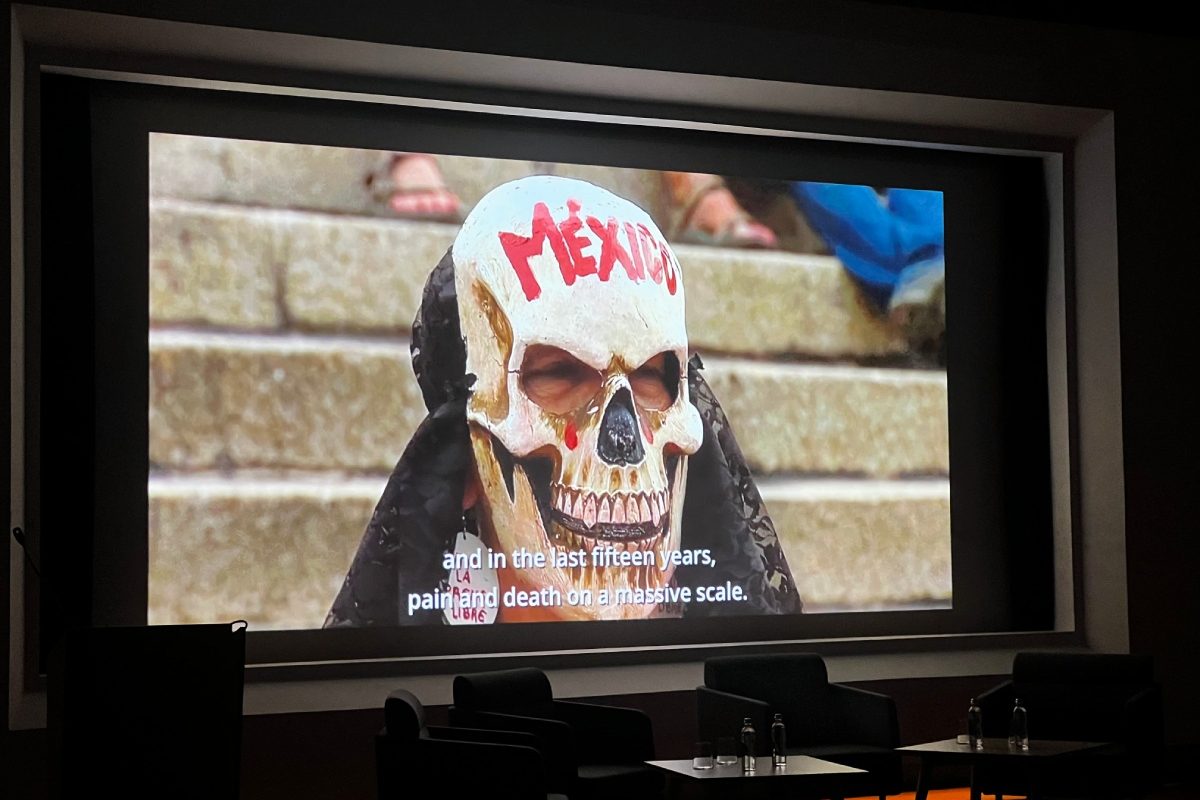

“It is a double silence. As citizens, we stop receiving information, and journalists are silenced,” said Santiago Maza, director of the recent documentary State of Silence. This film was screened during the 6th Films4Transparency initiative within the 2024 International Anti-Corruption Conference (IACC) in Vilnius, Lithuania.

This was a common topic of discussion at the IACC with Latin American journalists revealing the many strategies used by organised crime gangs or corrupt politicians to silence them.

Maza’s documentary reveals that various forms of coercion occur in Mexico, including frivolous lawsuits or accusations of criminal involvement. However, direct threats, such as intimidation and harassment, remain the primary method used to silence journalists, according to a recent report by Article 19.

When journalists are threatened, they often resort to self-censorship on issues crucial to their communities. Maza refers to the case of Jesús Medina, one of four Mexican journalists featured in the film. Medina, a rural journalist focused on water access issues, provided his community with vital information on how planned infrastructure projects could affect them. Medina stopped his work after receiving threats and seeing his house watched by strangers.

The IACHR report emphasises that the violence leading to these zones of silence is also tied to impunity, as fear among journalists grows due to unresolved crimes. “It is a pattern that allows aggressors to feel empowered to continue,” commented José Medina after the screening of State of Silence at the IACC.

Despite leaving his community through the government’s Mechanism for the Protection of Journalists in Mexico, José Medina criticised it as ineffective. Marcos Vizcarra from Sinaloa, another one of the journalists featured in the documentary, argued that it is not enough to simply remove journalists from immediate danger. Conditions need to be improved to allow journalists to carry out their work safely.

The Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) agrees, stating that high violence levels are partly due to Mexico’s failure to provide a safe environment for journalists and to take crimes against the press seriously.

Maza explained that he did not choose the name State of Silence by chance. It reflects both press freedom in parts of Mexico and the stance of the authorities. But despite this, the journalists strive to maintain hope.

“Dialogue must focus on modifying laws to benefit human rights and protect journalists,” concludes Jesús Medina, who now organises efforts to help other journalists at risk and mitigate the silence that follows these attacks.