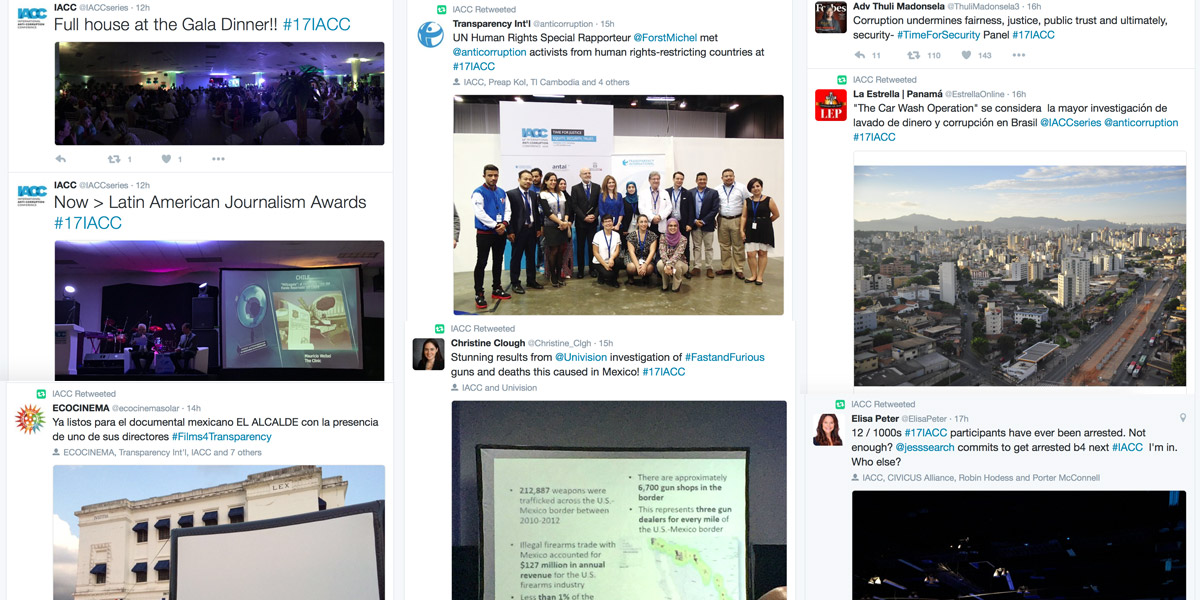

Time for Security Plenary – Photo: Mauro Pimentel

Journalists and human rights defenders need greater protection if they are going to be kept safe and free to continue the fight against corruption, experts have told an audience at the 17th International Anti-Corruption Conference in Panama City.

The murders of prominent activists like Honduran Berta Caceres and the threats many journalists around the world face as they do their job show that there remains much to do, panelists from the UN and other organisations told the “Time for Security” plenary at the IACC.

Both sectors face intimidation from governments and organized crime gangs, and are also being silenced by tough “security crackdowns” which are more about protecting power than keeping the public safe, they said.

Barbara Trionfi, from the International Press Institute, said some countries have been toughening up laws on press freedom and national security as they “have been able to manipulate the distrust and convince us that it’s necessary to increase surveillance.”

She said she was particularly concerned by regimes using security and criminal defamation laws to crack down on the press, and highlighted how in Turkey 140 journalists are now in prison for insulting the president or due to broad anti-terror laws.

Worldwide, she said more than 100 journalists have been killed every year since 2009, many of them because they were working on local corruption stories.

“There’s been an increase in violence. Why? Because it’s easy. It’s the best way to silence a journalist. Put them in jail and it’s complicated, a country can continue to come under international pressure. If they are killed, whether by the state or criminal groups it’s easy because there’s impunity.”

She said personal intimidation has also had a chilling effect on the media with threats forcing journalists to abandon sensitive subjects, or leave the profession altogether.

Michel Forst, the special rapporteur on the situation of human rights defenders at the UNOHCHR, said society needs to “better understand the causes of these attacks against human rights defenders and find new strategies to combat it.” Mentioning Caceres, an environmental activist killed earlier this year, and other human rights defenders, he said the community needed to remember “all those who have given their lives to secure a better future for us.”

Magdy Martinez-Soliman, the assistant Secretary-General of the UN and the UNDP assistant administrator, said that “there has always been a tension between liberty and civil society” but that history showed that fear can be “manipulated by governments that feel threatened”, giving them the legroom to impose tougher security measures on their citizens.

“We need to reject vehemently this idea that you have to choose between security and liberty. Since when? I want a government that does both. That’s the first thing – rejecting this false dichotomy, the false narrative that is offered,” he told the audience.

Going forward, he said it is important that “those of us that can defend those at risk, those on the front lines. We need to defend the defenders otherwise we lose the front lines and we will won’t have the capacity to bounce back.”

Jess Search, from the non-profit BRITDOC foundation, who was moderating the debate, said that while she agreed journalists and human rights defenders need more protection, “many journalists are quite lazy and just relate the views of government, they don’t challenge them.”

“The challenge,” she said, “is to do more, to go further.”

Laura Dixon is a British freelance journalist currently based in Bogotá, Colombia. She is a former staff writer for The Times and has written for The Guardian, Monocle magazine, Vice/Munchies, and The Pool. She lived in Chile after taking a Masters in Latin American Studies and has remained committed to reporting from the region ever since. She has previously received the Financial Times’s Sander Thoenes Award for young journalists with an interest in emerging democracies and the CSIS’s transatlantic media fellowship.

Twitter: @lauradixon