In the United States, the well-documented legal troubles of former president Donald Trump are a prime example of misinformation benefitting politicians. His recent multiple convictions for falsifying business records, amid a slew of other cases against him, do not appear to be denting his popularity ahead of presidential elections in November.

This is nothing new. Trump has consistently declared himself to be innocent of all allegations and said that he is the target of a politically motivated “witch hunt.” Among his base, this seems to be working. 80% of Republicans believed Trump was facing a witch hunt, according to one 2023 poll.

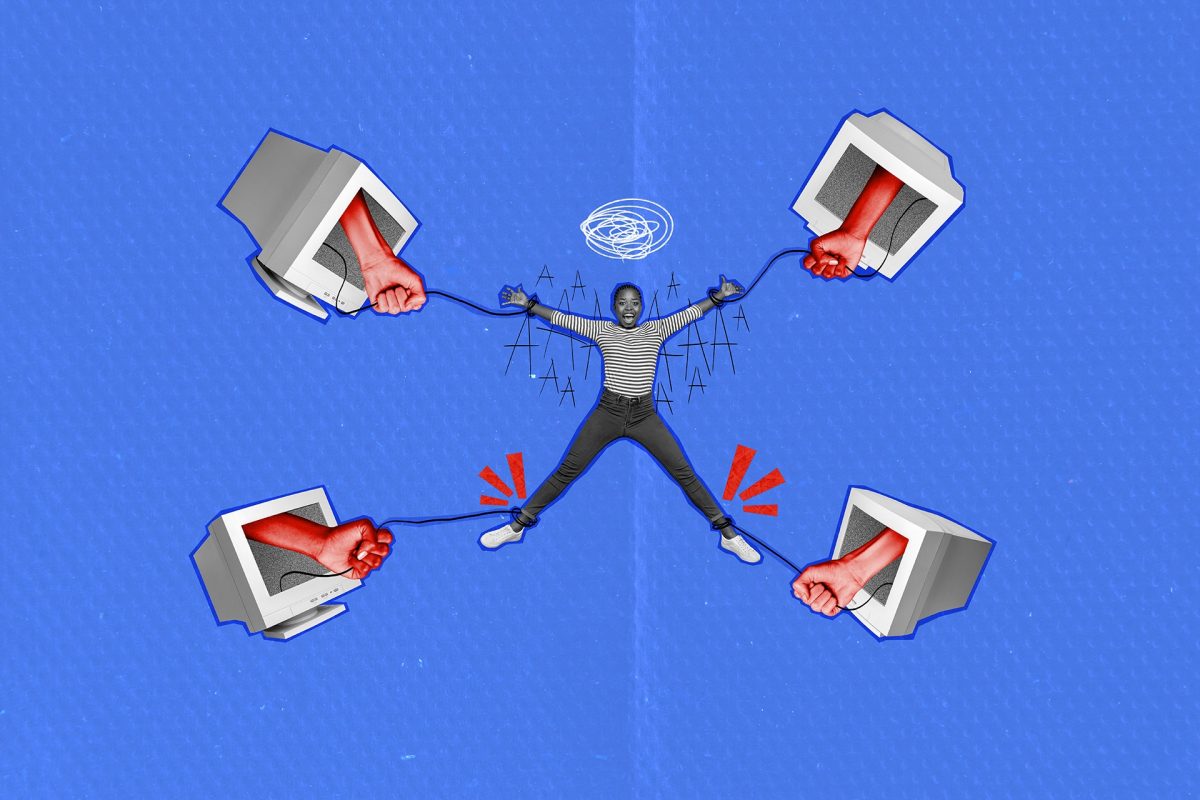

Dwindling trust in mainstream media and the spread of misinformation has only exacerbated the success of such tactics. Research suggests that many people suffer from news fatigue, after being bombarded with too much information. The spread of filter bubbles, where individuals mostly or only read news that aligns with their current views, is a growing threat.

“The best solution we have is to provide information so voters can make informed decisions. We can’t control the decisions they make, but we can lay out all the facts for them,” said Brandi Swicegood, Executive Director of Sunlight Search, during a panel at the International Anti-Corruption Conference (IACC) in Vilnius, Lithuania on June 19, 2024.

For Swicegood, certain politicians continue to thrive because they have a loyal follower base and a unique way of attracting people. Getting inside filter bubbles to raise awareness about their questionable backgrounds becomes particularly challenging, panellists agreed.

“The information you share often becomes part of the polarisation process within a polarised ecosystem. People on the other side don’t care about the information itself. It doesn’t matter to them,” said David Schraven, co-founder of independent media outlet Correctiv.

Panelists agree, misinformation also spreads rapidly in rural areas, for example, making it difficult for national or international outlets to reach audiences quickly.

While agreeing there is no instant solution to this problem, the experts at the IACC suggested it was vital to tap into the power and influence of local media. In some places, trust is often far higher in local newsrooms than in their national counterparts, studies have shown, and these may be more effective at debunking misinformation.

“Try to form alliances with local media. They don’t have the reach, resources, or privilege that we [larger media] have,” said Claudia Baez, CEO and co-founder of Colombia’s Cuestión Pública.

The panel considered how this problem affects different countries, including Mexico.

In Mexico, politicians at the highest levels of power have been dogged by corruption allegations. Even the latest president, Andrés Manuel López Obrador promised to reduce corruption but was then reported in an investigation by ProPublica to have what US drug enforcement agents believe accepted US$2 million from drug cartels in return for favours during his 2006 campaign. López Obrador strenuously denied the claims.

Transparency International’s 2023 Corruption Perceptions Index ranked Mexico 126th out of 180 countries. And there are doubts whether López Obrador’s hand-picked successor, Claudia Sheinbaum, will be any better at dismantling Mexico’s corruption networks.

“The decisions are complex. Having information to contrast helps hold people accountable for their decisions,” said Mariel Miranda of Transparency International Mexico.

In Mexico and elsewhere, experts state that corrupt politicians are maintained and supported because of weak state institutions and strong patron-client relationships. So as long as these leaders can meet the needs of their cronies, they will retain key political support.