In 2018, a court in Osun, southwestern Nigeria, sentenced university lecturer Richard Iyiola Akindele to two years in prison for sexual harassment. At the time, this ruling was seen as a significant step towards combating sexual harassment on campuses in Nigeria.

But five years on, similar allegations surfaced at the University of Calabar, where law students accused their dean, Cyril Ndifon, of sexual harassment. Despite his denial, the university authorities suspended him and a panel established by the institution concluded the charges were true. Ndifon is currently on trial for these allegations.

There are numerous reports of university lecturers demanding sex in return for favourable grades. However, the true scale of the problem is often obscured due to underreporting, fear of retaliation, stigma and the lack of safe reporting tools. A World Bank report found that 70% of female graduates in Nigeria have experienced sexual harassment, mostly from lecturers and classmates. In the past five years, at least 39 lecturers have been indicted or dismissed for such misconduct.

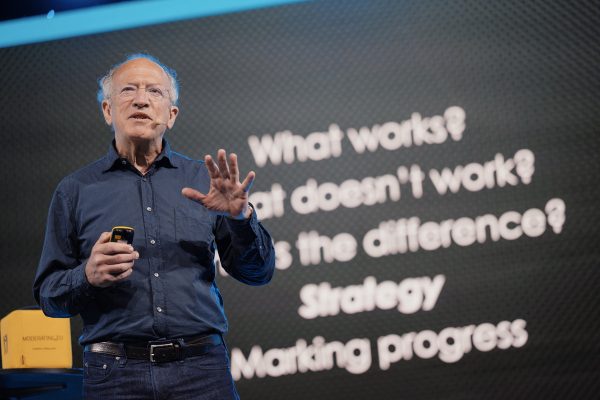

At the 2024 International Anti-Corruption Conference (IACC) in Vilnius, Lithuania, experts discussed why this problem persists. They noted that many victims don’t trust the system to protect them from repercussions.

“Several cases of this nature go unreported because victims fear victimisation and stigmatisation within the university,” said Lilian Ekeanyanwu of the International Federation of Women Lawyers (FIDA) Nigeria chapter.

According to FIDA, only about 30 out of over 265 universities in Nigeria have policies to combat sexual misconduct. “But there is no clear evidence of how these policies are implemented and whether students even know these policies exist,” Ekeanyanwu said.

The scale of the issue was highlighted by a 2019 BBC Africa Eye documentary, which exposed sexual harassment at the University of Lagos in Nigeria and the University of Ghana in Accra. Two years later, the University of Lagos fired the two lecturers involved in the documentary for soliciting sexual benefits.

Even when universities do take action, it is often limited to dismissing or suspending lecturers. Committees or panels established to probe allegations often fail to address the problem comprehensively.

Experts at the IACC argued that these measures have not eliminated systemic abuses in educational institutions or provided a safe reporting environment. Instead, they have allowed a disturbing pattern of abuse of power to continue, supported by institutional failures to protect students.

Creating safe and anonymous reporting mechanisms is crucial. “Each institution must have a special reporting individual or centre that is sufficiently private and known to students,” said Huguette Labelle, former chair of the board of Transparency International.

Labelle also stressed that contracts for university professors and teachers must clearly state that they must act with integrity and prioritise student protection.

Collaboration with the person reporting harassment is key to addressing this issue. Universities often fail to provide updates to the victims or involve them in the investigation process.

Guaranteeing anonymity is also a challenge. “Even if the victim is said to be anonymous, if there is only one victim, the perpetrator knows who reported,” Labelle noted. To address this, multiple reporting channels should be established.

“It is important to have several reporting options so that victims don’t have to report to someone who might be the perpetrator,” said Jennifer Sarvary Bradford from the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime’s Corruption and Economic Crime Branch.

The issue of sexual harassment in universities has not gone unnoticed among policymakers. In July 2020, the Nigerian Senate passed a bill to tackle sexual harassment, but it has yet to receive presidential assent. The bill proposes a two-year prison sentence for university lecturers found guilty of sexual harassment.

Clear, safe and accessible reporting channels, along with assurances of safety, can encourage people to come forward. Additionally, universities and schools need to provide support systems – including academic accommodations, legal assistance, counselling and mental health services – to help victims heal and regain their confidence.

Addressing persistent allegations of sexual harassment against lecturers requires raising awareness about the rights of students and the obligations of educators, while also creating a safe learning environment for all.