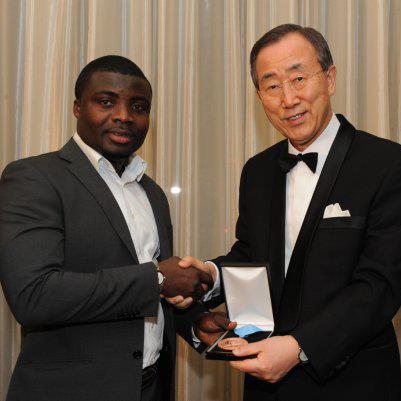

Samuel Agyeman receiving his award from former UN Secretary General, Ban Ki Moon (Photo Credit: Samuel Agyemang)

In 2013, one of Ghana’s finest journalists resigned from his job. He also stopped working in the media industry altogether and took up a position as a public relations manager at the Ghana Ports and Harbours Authority (GPHA).

Samuel Agyemang’s resignation was not planned. His passion for journalism was infectious. He loved what he did, and was good at it. In 2009, Agyemang was named a United Nations (UN) Dag Hammarskjöld Journalism Fellow and was presented with the Ortega Memorial Bronze Medal by the UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-Moon for reporting on the UN in New York. That same year he was named Journalist of the Year and received the award for TV Features Reporting from the Ghana Journalists Association (GJA). He was later also named the Thomson Foundation Journalist of the Year by the Commonwealth Broadcasters Association.

So why would a journalist with such level of excellence leave the media? Did he take a bow when the proverbial applause was loudest? No. He was pushed.

“This is because I had prepared a story ready to be published in the news, but the station’s management warned me not to use the story on their network. I begged them to show the story in the interest of Ghana, but I was told my request was being denied in the interest of business,” Agyemang recounts.

“To prove my resolve to serve the country in truth, I published my story on YouTube and shared with credible and serious media outlets like Citi FM. Then I immediately resigned. I declined any call and advice to return to my network to signal the fact that I value integrity.”

Samuel Agyemang’s story turned out to be one of the biggest corruption scandals exposed in Ghana in 2013. His story was about a shady contract that the Ghanaian government awarded to an IT company named Subah Infosolutions Limited “to monitor revenues from phone calls on behalf of the government. It turned out, they never did independent monitoring by themselves but were being paid from 2010 to 2013,” Agyemang explained.

This company was paid more than €26 million for practically doing no work.

The other major corruption story that year was the Ghana Youth Employment and Entrepreneurial Development Agency (GYEEDA) scandal which I uncovered. Investigations into this story revealed that out of the nearly €438 million which was allocated to the employment programme between 2009 and 2012, about 80 per cent was stolen through shady business deals with some of the most powerful businesses in Ghana.

The GYEEDA expose led to the cancellation of all the contracts, except one. The programme was suspended and parliament passed a law, the Youth Employment Act of 2015, to regulate the programme in order to curtail the wanton dissipation of public funds in the future. Two people were charged and jailed for corruption while a dozen others lost their jobs. The topmost government officials who signed the corrupt contracts and their accomplices in the private sector, however, were not held accountable.

Unlike the GYEEDA scandal, however, the Subah scandal did not receive any government attention apart from an ill-fated committee that was set up to whitewash the deal. The Subah contract was however terminated in 2018, and the communication’s minister revealed exactly what Agyeman had exposed five years earlier.

“Mr. Speaker, since traffic was never monitored in real-time, these companies collected the data from the same servers as the NCA (National Communication Authority) verification team and so inevitably, the monthly traffic data collected by the NCA from the network operators for free was substantially the same data presented by Subah and Afriwave [another company engaged later in 2016] for which the latter companies were paid approximately $2.6 million per month. Mr. Speaker, we were in effect paying for no work done,” Mrs. Ursula Owusu-Ekuful, the Minister for Communications and MP, told Parliament on June 1, 2018.

The GYEEDA and Subah scandals have some striking similarities, and specifically, the same point of convergence.

The committee that was set up by the government to probe the GYEEDA scandal concluded that the shady contracts were “heavily skewed” in favour of companies belonging to Mr. Joseph Siaw Agyepong of the Jospong Group of Companies, Mr. Roland Agambire of the AGAMS Group of Companies and Mr. Seidu Agongo of the Zeera Group of Companies.

Subah Infosolutions is also owned by Joseph Siaw Agyepong and forms part of the Jospong Group of companies. But the point of convergence of the two scandals does not end there. The three businesses named in the two scandals, after being shaken by the media exposes took aggressive steps to own media entities.

The Jospong Group bought Metro TV, the station that refused to broadcast Samuel Agyemang’s investigations on a Jospong company, leading to his resignation. The AGAMS Group started The Telegraph newspaper and acquired half a dozen radio frequencies to operate radio stations across Ghana. The Zeera Group ventured into the media space, establishing notable brands including Accra Radio and Class FM.

These are not the only businesses that have ventured into the media space. In fact, the media seems to be dominated by entrepreneurs whose core business is not the media. The other major owners of media entities in Ghana are politicians. In a nation where corruption remains the biggest threat to development, and the media appears to be the only hope in fighting the canker, this phenomenon certainly does not portend well for the health of Ghana. Agyemang wants the Ghana Journalists Association to act to prevent what he calls the total take over of the media space by these businesses. But it seems the GJA itself has not been spared.

In 2017, the Dean of the School of Information and Communications Studies, at the University of Ghana, Prof. Audrey Gadzekpo, described the GJA in its present state as a “victim of corporate capture.” According to her, “instead of defending the interest of the members, the reason that it [association] exists, is [to] defend the interest of big business.”

She was reacting to GJA issuing a press statement condemning a journalist for exposing fraudulent contracts awarded to companies belonging to the Jospong Group. One of the contracts, which was awarded for around €65 million, was actually inflated by over €27 million. The GJA did not state that the report had any factual inaccuracy or that it breached any ethical code, but it found it convenient to issue the press statement.

In January 2019, the government confirmed the cancellation of the €65 million waste bins contract.

The corporate and political capture, as well as other weaknesses in the media industry, have conspired to pose a mortal threat to the fight against graft. With the emergence of social media, however, there is hope. Agyemang’s documentary enjoyed social media circulation until it became the most topical issue on mainstream media. In recent times, some of the major corruption issues in Ghana are broken on social media.

Civil society groups now resort to social media to share their findings and documents and with time, it dominates mainstream media. The head of Ghana’s most outspoken think tank, IMANI Africa’s Franklin Cudjoe, recently said that social media proved effective at times when mainstream media shied away from his corruption crusade.

The latest allegation of corruption that was spearheaded by social media involved some questionable expenditure and contracts at the Ghana Maritime Authority. In October 2016, it was the most topical issue covered by media Ghana, but it started on social media by a musician and political activist, Kwame A-Plus.

The danger of relying on social media is the reliability of the information. The doctoring of documents, misrepresentation of facts and lack of proper verification make the work of mainstream media and investigative journalists indispensable. But with the weak implementation of the Whistleblowers Law and the refusal of parliament to pass the Right to Information Bill, which has been pending for the past two decades, it appears leaking official documents on social media has become a phenomenon, which corrupt officials dread.

It has its negative consequences, but it currently serves as an anti-corruption crusader that cannot be compromised or suppressed.